Stone

Early in her career Mary adopted standard carving practices: roughing out a larger block; refining shapes and surfaces; creating lively marks; polishing. This approach, taught by John Skeaping, is evident in works such as Ram’s Head 1934. But it was Ossip Zadkine who had the most lasting influence. Her time studying with him in Paris gave her confidence to explore freshly worked surfaces and geometries that echoed the Romanesque carvings she admired.

Mary delighted in the moment where her hand and chisel first met the ‘serious resistance’ of stone, which became ‘an enabling force rather than a hindrance’[1]. From that moment she created each individual sculpture using a range of tools and a repertoire of carving techniques.

With the rebuilding of Britain after the Second World War Mary successfully applied for a number of architectural commissions. She made stone sculptures for new schools, universities, teaching hospitals and Harlow New Town.

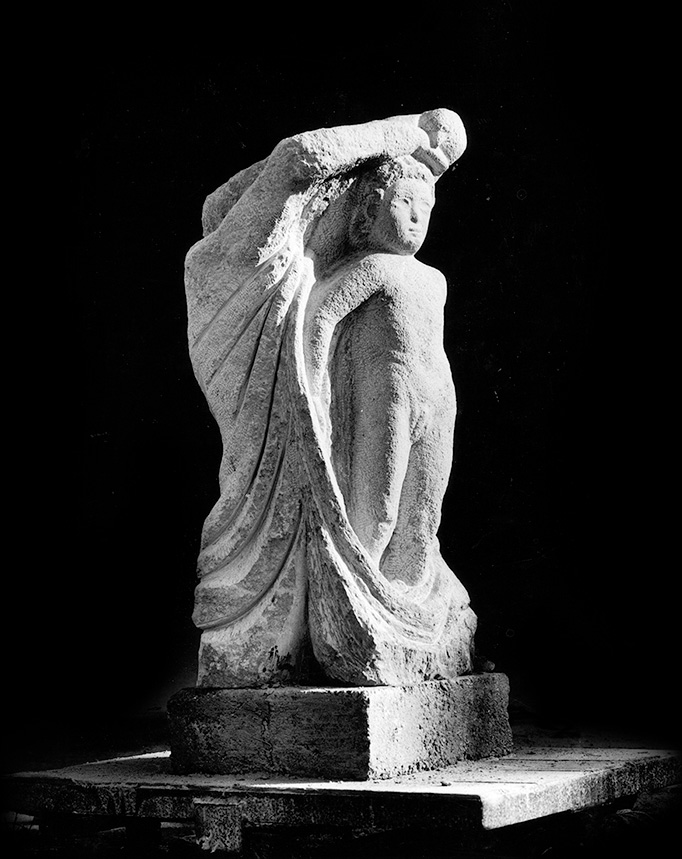

After Hilda died, Mary travelled with a friend around Greece and the former Yugoslavia to examine the ruins of antiquity and their classical carvings. Zadkine’s influence became fused with the further possibilities of classicism, as seen in Musician 1955. This sculpture was displayed at the Royal Academy, resulting in a commission for Guildford Cathedral from its architect Edward Maufe.

Opportunities for commissions and exhibitions dwindled as new art styles became popular in Britain, and Mary devoted more time to teaching and running Dunshay. However, in the 1970s she focused her energies once again on sculpture. A successful exhibition at Dorset County Museum in Dorchester gave her confidence to go forward.

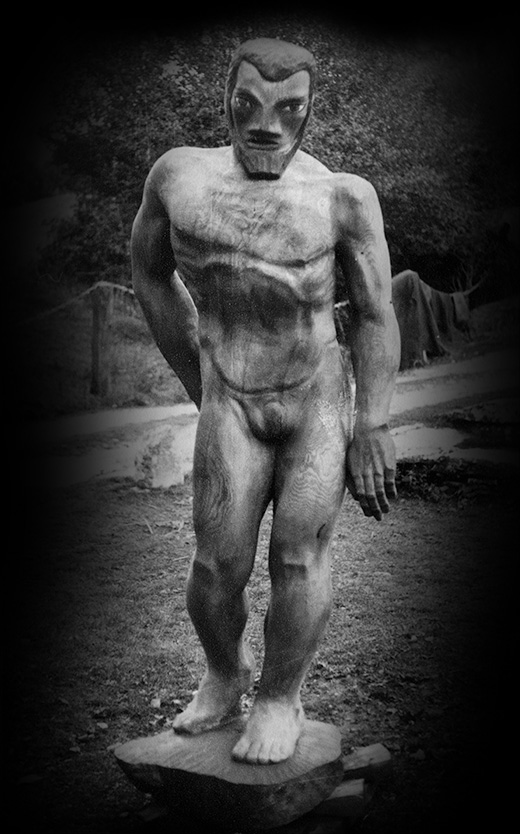

Purbeck Quarryman 1999 is among Mary’s later works. The commission came two years after she was made an Honorary Freeman of the Ancient Order of Purbeck Marblers & Stone Cutters, one of the few women on whom this honour has been bestowed.

[i]Annette Ratuszniak, Mary Spencer Watson, Sculpture, Catalogue Raisonné p.59,

Terracotta

Mary was taught to model with clay at the Royal Academy Schools. This technique enabled her to build a sculpture ‘rapidly and with spontaneity’[1]. However, she did not enjoy using clay: ‘It is too free, it’s too much like me; I think I need resistance, but it does give one three dimensions’[2].

The teaching of sculpture at this time was based around figure studies and set pieces. Her RA student disc allowed her to handle artefacts in the British Museum, where she often asked to examine the small Tanagra terracotta figurines. These Greek figurines also feature in a book, ‘Diphilos et les Modeleurs de Terres Cuites Grecques’ by Edmond Pottier, owned by Hilda. The figurines were made from the fourth century BC, and are thought to represent people and moments in everyday life. Although mould-cast, a method very different from modelling, Mary was inspired by the naturalistic movement of these small sculptures.

Her first solo exhibition at the Mansard Gallery in Heal’s, London, included figures and plaques in terracotta. Peyton Skipwith noted the Tanagra influence in a portrait of Vera Brookman 1934, with its ‘exquisitely modelled small head’[3]. The development of Mary’s style and her growing interest in truth to materials is evident when the terracotta portrait is compared with later clay works such as Man with Horse 1950. The portrait is realistic and delicate, using fine art clay, whereas Man with Horse is expressionistic and made from local brick clay. The coarse clay sculptures were fired either in the kilns of Sandford Pottery or Swanage Brick Company in Dorset.

[1] Elizabeth Rankin & Robert Hodgins, The Concept of Truth to Material, 1979, p.4, [2] Ratuszniak, 2004, p.54, [3] Ratuszniak, 2004, p.55

Wood

Mary preferred to work with native woods such as ash, boxwood, elm, walnut and yew. At times she used timbers from the grounds of Dunshay Manor, and even former roof beams from the house.

Skeaping taught her to use an adze to remove mass from the block, followed by chisels and sanding materials to create forms with smooth surfaces and little evidence of tool marks. Mary would make a small, unfired clay maquette to give an approximation of the final shape. Working with this in mind on the larger block she responded to the natural limitations, grain and colour of the wood to bring out its inherent qualities. This resulted in expressive polished forms, such as Wooden Figure 1934/35.

Zadkine encouraged Mary to ‘celebrate the mark of the tool’[1], and it was in Paris that she became interested in the geometry of Cubism alongside notions of archaic beauty, as seen in Descending Angel 1938/39. The tension between archaic beauty, modernism and her interest in the Romanesque were an enduring inspiration.

Many of her woodcarvings were made in the round, but Mary also carved in relief, still exploring the potential for animation and drama. Beauty Hastens to the Dying Beast 1991 creates a sense of movement through the layering of the figures, but the deep cutting and resulting balance of light and shadow bring the scene to life.

Mary refined her working methods throughout her life. In later years she developed a lighter touch as seen in Dancer 2004, where she deliberately left the viewer to imagine the form and movement of the dancer’s hands.

[1] Susan Compton, Mary Spencer Watson: Sculptor, 1991 p.6